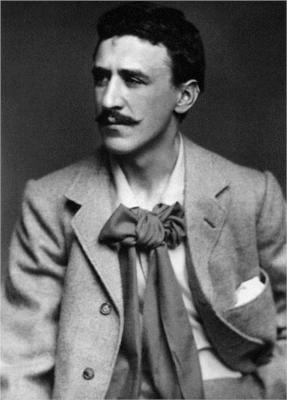

Mackintosh at the Willow, A Wee History – Part 10.

The Willow Tea Rooms Trust purchased the premises at 217 Sauchiehall Street in July 2014. An extensive project began to assess the current state of the building, source all original designs and any photos to help create a faithful reproduction for new visitors to enjoy. The building closed fully in 2016 and the last two years have seen an intricate plan come together as craftsmen and experts from across Scotland, the UK and North America shaped the building.

The tea rooms have been restored as closely as possible to their 1903 original space, while making limited concessions to the needs of a modern tea room. The only area not included in the restoration project was the Dug Out which would have spanned in to the adjacent building – something that is owned by another company and inaccessible for restoration.

The original 1903 design took less than a year to complete. This was an ambitious project, for Glasgow’s busiest, most salubrious street. A commentator said of it in 1901 that “Sauchiehall Street is the brightest and gayest street in Glasgow, the only street of pleasure. It has more painted buildings and gilded signs than any other.”

Mackintosh took a typical Glasgow tenement and completed renovated the whole space to suit the tea room and artist!

The entire frontage has been restored by hand. The Trust discovered that at some point when the building moved from being a tea room to a department store that the windows had been reset to a more shop friendly frontage and actually used an original chair to do a size comparison with old photographs to get the right height. The frame has been created with a single piece of Douglas fir. Two roundels are still to go in at the top. The entire depth of the frontage had to be altered as throughout the years it had been cast in rendering multiple times.

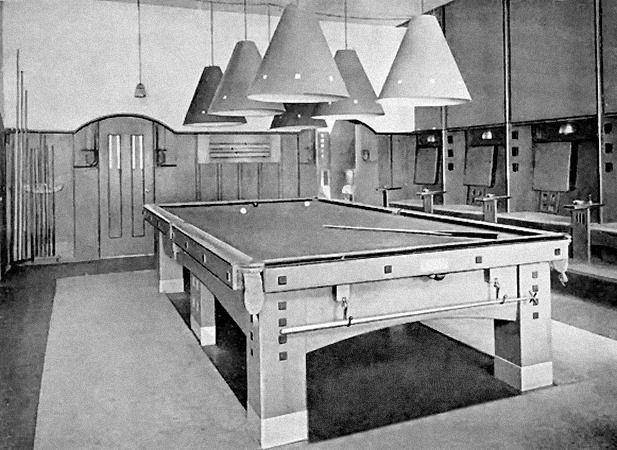

The three floors are returned to their original purpose as tea rooms, with the Salon de Luxe at the centre of the building and the Billiard Room above.

215 Sauchiehall Street has also been restored but embracing modern architecture. In the basement below the shop there will be a Learning and Education Centre, which will have 2500 schoolchildren visiting per year (approx.) mostly from deprived areas. Thirty schools have already been engaged with and will be coming on site to learn artistic methods inspired by Mackintosh like print making and panel work.

The wooden panelling in the front entrance hallway and Front Saloon has been completely restored; with part of the original at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery used for reference.

Luckily The Willow was professionally photographed to be featured in the Decoratieve Kunst Magazine so there was a set of photographs that the team were able to work from. They were however all in black and white so careful analysis had to be made to determine colour schemes and varnishes.

The friezes are both original and have been restored having been covered by shop fittings. A lot of the original features in the building were partially hidden or covered up with shop panelling so remain but had been damaged. The Green detailing was added by Jo Hormuth from Chicago Architecture Company, with details taken from the Decoratieve Kunst photos. She also worked on the rear panels and did the rose pink stencilling and the curtains which are all hand painted.

Mackintosh designed six individual chairs and stools for The Willow, in addition to the fitted seating. In the front Salon we see a version of his famous ladderback chairs, originally designed for Kate Cranston’s Argyle Street premises.

The Willow pattern designed by Burleigh of Middleport is unique to the Mackintosh at the Willow and is based from original pieces still held in collections and from photo analysis.

The Baldachinno (from the Italian meaning a canopy, usually placed over a throne or altar) cast is in four pieces. The process of it being made will be in the interactive exhibition for visitors to appreciate. The final piece of the Baldachinno, it’s glass and copper bowl is still to go on and will have glass test tubes with flowers inside. (Apparently for the first six weeks that the tea room was open Mackintosh would come in each morning to personally arrange the flowers!)

Copies of the original runners have been created by taking thread samples from the original carpet along with the photographs in order to get the colour and the weave right. These were made by Grosvenor Walton from Kidderminster in England.

The stairs are original, but the banisters were taken out and replaced. Several of the green glass droplets are original, with only a couple needing to be replaced. The older ones are slightly duller in comparison to the newer glass but they are otherwise fine reproductions. The Willow Tea Rooms Trust decided not to polish the old ones as it shows their history and beauty, and the new ones will not be overly cleaned so that they may age alongside. The glass at the banisters was added for safety.

The floors are original and restored as best as possible. The original fireplaces were uncovered as part of the restoration. There was a conflict amongst the Trust between preserving them historically and staying true to Mackintosh and Cranston’s vision for the tea rooms; they would not have allowed for any kind of shabbiness and certainly not the cracks you can see on the façade. The decision has now been made to repair and restore them to how they would have originally been but to protect them further the Trust have decided to place gel, decorative ethylene fires which won’t emit heat but will give the feel of the space.

In the Back Saloon,there was a servery in this position, which we know from a drawing from 1923 (when they asked for planning permission to take out the original). To serve modern health and safety regulations and the requirements of a modern tea room it has been extended by 400mm.

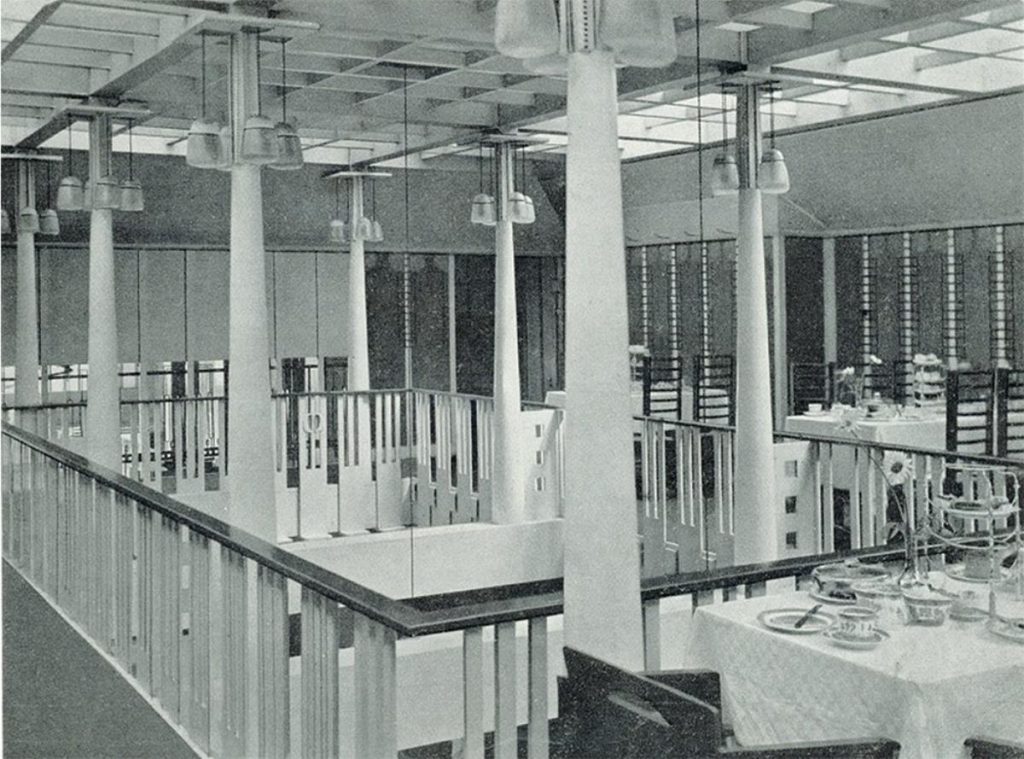

The back salon was designed to feel like a cosier, more personal space, the undergrowth to the wood above. From this point we can see the effect of the cantilevered balcony, with the tree-like columns and suspended lighting fixtures cascading down like branches. As with the balcony at Queen’s Cross Church this was a prototype for the suspended balcony of the GSA’s library.

We also have here a recreation of Kate Cranston’s cashier’s chair, the original for which is at the Glasgow School of Art. A lot of research was done in conjunction with Mackintosh collections around the city and world to make sure reproductions were done as accurately and faithfully as possible. This chair carries on the Willow theme in its symmetrical high back, and allowed Ms Cranston to survey the tea room in her wide skirts, while keeping the money safe in its hollow base.

The rail in the gallery was added for safety. Because it was a historical building it wasn’t a requirement from building control but because the original is so low it was decided that it would be the best thing. One of the biggest challenges was how to transport hot food around the building as regulations do not allow for it to be carried upstairs, so the dumb-waiter and servery have been expanded to comply with modern regulations.

The lights used here are energy-efficient, modern Edison bulbs which mimic the more golden lighting that would have been common in 1903. The whole space would have been a marvel of light as most public and private buildings in Glasgow still used gas light. Only two per cent of homes in Glasgow were lit by electric light. (Interesting fact: It was a Glaswegian industrialist Lord Weir who developed the national grid in 1926) The light levels are not ideal at the moment so it is still to be decided if they will stay once the full natural light has returned.

The roof skylights had been altered since Ms Cranston’s time and had to be completely rebuilt to where Mackintosh intended to more accurately track the light. As is evident with his own house over in the West End, Mackintosh interiors respond to how the light works in the space, the direction of sunlight and how it changes during the course of the day is very important.

The wooden lattice ceiling had also been altered and was unsafe. Although the previous restoration in the 1980’s had tried to do justice to the design, it was too low and structurally unsound, so it too had to be restored. Tthe stencilling here was again by Jo Hormuth.

One element which hadn’t been touched was the fireplace, which mostly just needed some cleaning of the glass.

Moving through to view the stairs, all the colour matching for paintwork has been done by analysing original paint samples which was undertaken by Liverpool University.

The paintwork on the stairs was originally silver, this was applied but proved challenging because it was reflective and showed up every mark, was very unforgiving and was difficult to maintain. So now the grey on the wall is the closest shade to mimic the silver, and it is still being decided if they will put the silver back on.

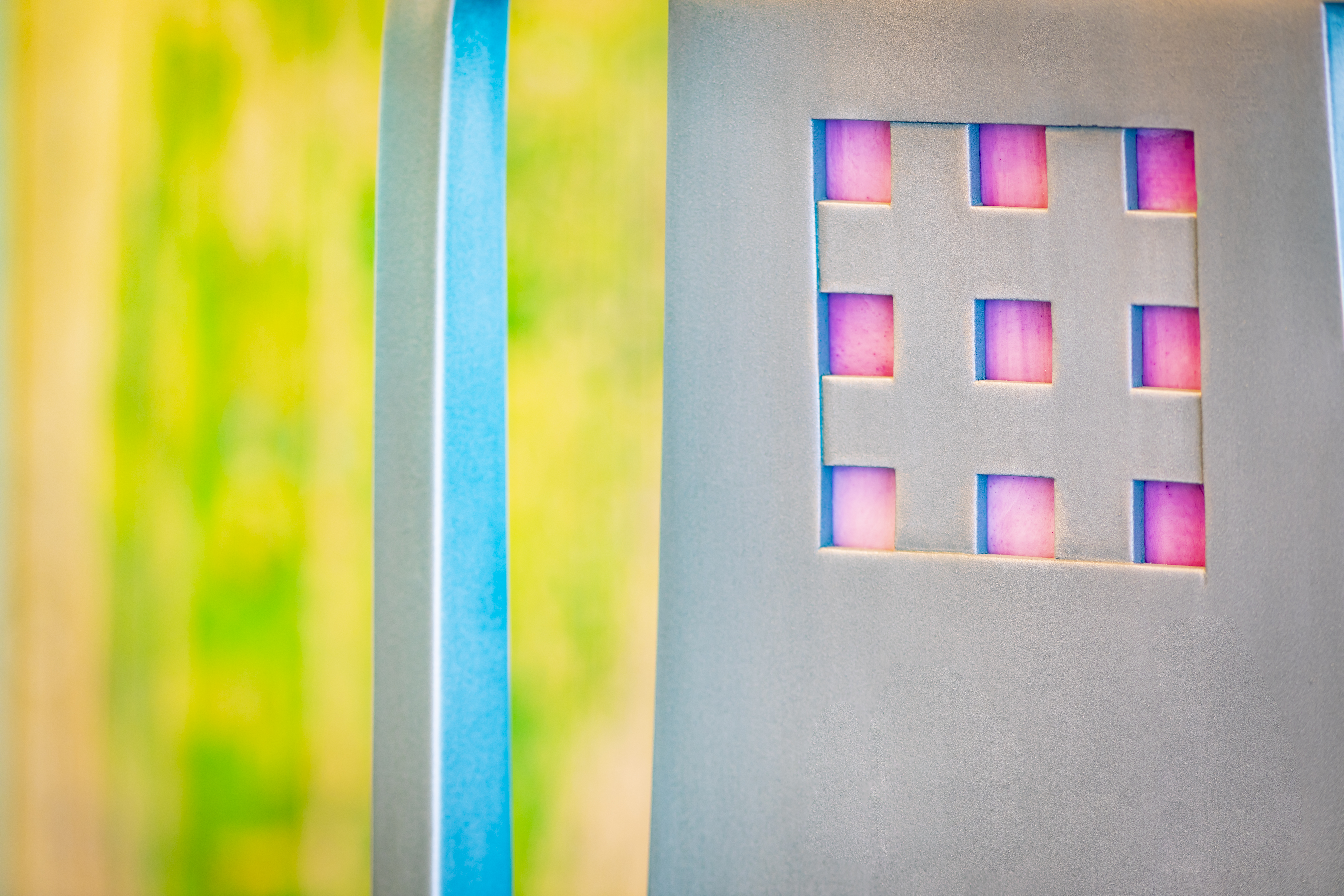

The green glass squares in the banister panelling are original, and protective glass and handrail are still to be added along with carpet runners, but it was felt, until the building is completed that they would be spoilt by the heavy tread of builders.

The change in light from the stairway to the Salon de Luxe is dramatic, almost to instil a quiet before the spectacle of the main room. It was a penny extra to dine in the Salon De Luxe, as it was meant to offer a luxury experience where women might entertain guests outside their houses.

Today it has nearly been completely restored back to the

original, with only the carpet to be replaced. The windows were restored by the

same window makers (Crittall Windows of Helensburgh) and ironmongers who worked

on the original tea rooms also helped with the handles. It is even the same

family but three generations on! The window setting had actually been altered

by 9 inches, disrupting the smooth façade of the building and was entirely

restored to its original setting. This proved more difficult than first

envisaged as the structure had been cut into and needed replacing to ensure its

structural integrity.

The Chandeliers were recreated by Cannon MacInnes of Glasgow again with

painstaking attention given to the photos from the time. The first sets of

glass baubles created for these reproductions proved too perfect as they didn’t

have the correct bubbles seen in the photos so they were sent back and reset.

Again they aren’t quite finished as they need their full Edison bulbs to really

gleam.

In 1903 each chandelier was lit by 19 electric bulbs, which danced light off the ceiling and reflected it around the mirrored glass frieze. Cooper & Co are listed as supplying 468 clear and green glass drops and 300 clear and ruby glass beads. These came in six different shapes and were suspended on wires from metal hoops and a ceiling plate to form each chandelier.

At a cost of two pounds and 16 shillings each, the high-backed chairs for this room were substantially more expensive than the ladderback chairs used elsewhere in the tea rooms which cost only 17 shillings and sixpence. One of the reasons for this was the unusual finish, which was both labour intensive and expensive. Mackintosh never reproduced this finish, making these unique examples of Mackintosh style.

The eight high-backed chairs, finished with silver-coloured aluminium flake, upholstered in luxurious purple velvet and inset with nine squares of pink and violet glass, were grouped formally around four central tables. These tables were precisely placed within the geometric pattern of the carpet. As seen with the famous ladderback chairs of the Argyle Street Tea Room these high-backed chairs created islands of privacy. This furniture was created by another Scottish artisan called Kelvin Murray from Character Joinery.

Other elements noticed in the photos and incorporated are the bead work on the side panelling; this is in a very definite pattern, (3;2;1) but we’re not sure of the significance.

The Gesso Panel, was recreated by Dai and Jenny Vaughn who did all the gesso work at the House of an Art Lover.

The velvet fabric of the seats was another puzzle for the Trust to unravel. An original sample of the velvet was found in Margaret Macdonald’s workbox, which helped guide the advisory panel through the multitude of options for velvet. This velvet came from Italy.

All the furniture is stamped Mackintosh at the Willow for authenticity. They form part of a collection that will eventually be deemed antique as they have followed so closely the original design and process. They are exact replicas and the only thing about the making process that doesn’t follow the original process is the glue which was used, modern synthetic instead of animal glue.

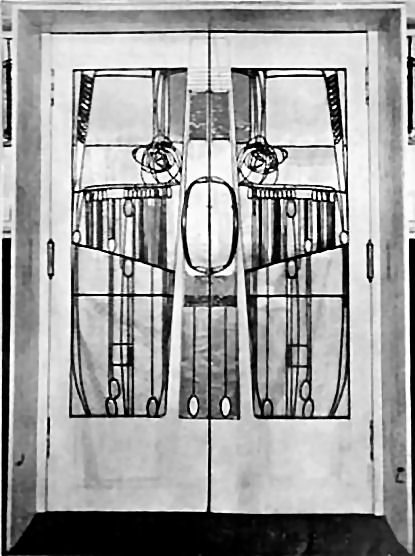

The doors can be admired from either side and are replicas of the original which will be displayed in the exhibition space. They are beautiful iron and glass design which almost carries the tree motif to extreme.

The Salon de Luxe can now be used as a space for private dining and events a large servery has been placed to the right of the room to accommodate the dumb waiter system that transports food from the kitchens in the basement.

The Ladies Powder Room was this was used as a kitchen and serveryin the 1980’s. Some chairs and decorative elements are still to be added but the wood panelling is original.

The glass of the windows in the Billiard Room is largely original but where it was replaced the Trust were able to use the original ironmongers and they were able to match the blue glass in the window with the original as some of it still existed in the stockroom of the original ironmongers. The good thing about Mackintosh is that he frequently over ordered, but was notorious for not paying for the excess if it wasn’t needed! It has worked in the restorers favour though as they were able to source some of these all important leftovers!

Many specialist glass and iron mongers emigrated from Scotland and the UK the USA and set up their foundries, taking their specialist knowledge with them. Mackintosh imported a lot of materials from the US, and despite the long travel times (6 weeks by ship) there was a dialogue between the UK and US which fostered architectural influences.

Nancee Rogers

Thank you for this lovely history about MATW! I wanted to comment that the willow originally used in the tearooms by Miss Cranston was the Standard willow pattern. We know Adderley pottery supplied some it. Burleigh used to make Standard willow pattern, but after WWI, they wanted to introduce a fresh look for willow. In late 1923, they created what is now known as the Burleigh Dillwyn willow pattern, which is slightly different than Standard willow.

It’s wonderful that you chose to use this version of willow in the current tearoom! Burleigh is the only remaining pottery to use the original tissue transfer method of printing that has been done since the company began in 1851. The pieces are crafted by hand using time-honored techniques. I appreciate both your company and Burleigh for keeping these wonderful slices of history here for us to enjoy today. Thank you!