Mackintosh at the Willow, A Wee History – Part 5.

This week we will be focusing on one of the main decorative themes at Mackintosh at the Willow, the repetitive square. This simple shape is crucial to unifying the building as a whole and is a key design feature throughout the tea room.

Visitors are presented with the square motif upon arrival, as the building frontage is adorned with black squares contrasting the brilliant white background of the buildings front. The frontage of Mackintosh at the Willow is striking today but in 1903 it would have been quite a spectacle. The white painted render on the façade would have stood out against the neighbouring darker building, drawing the eyes of passers-by. It is asymmetric and holds clearly distinguished levels which are defined by varying stylistic techniques. For example, the ground level has been pushed back off the street while the first-floor window has been curved outwards to emphasize the importance of the Salon de Luxe. These features are united by the white rendering, but also by the frame of squares that highlights the edges of the structure and the window panels of the ground and third floors mimic this linear shape.

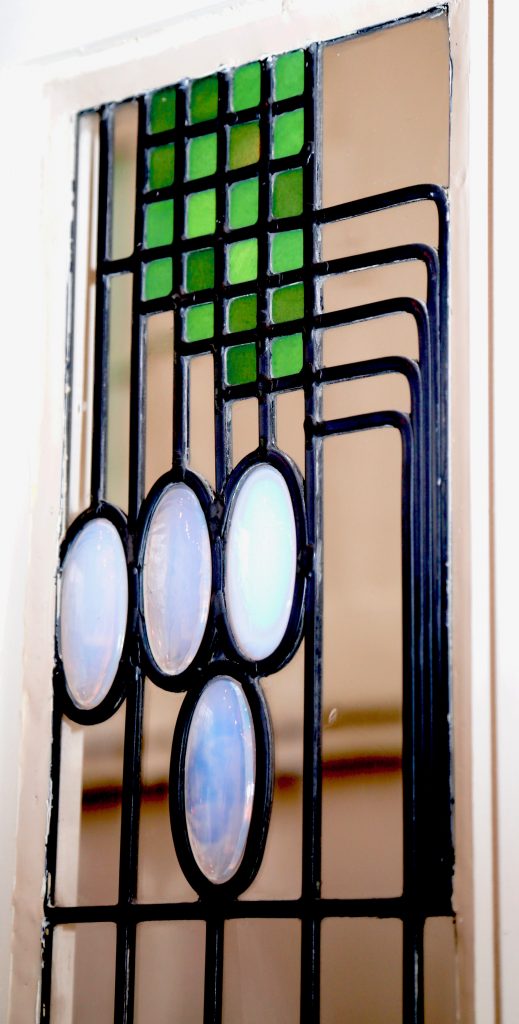

Mackintosh at the Willow employs the square motif in a similar manner to the willow theme displayed throughout. The visual elements link each room to create a true Gesamtkunstwerk or ‘total work of art’, whilst allowing the various spaces to retain their individuality. The square pattern is displayed in many ways. We see it in the ladder-back chairs, chequer board motifs, trellises, fragmented willow trees and glass tesserae.

Before the 1900’s Mackintosh’s work adopted a softer approach to form, with flowing lines that embodied the dream-like qualities of Symbolism and the natural world.

Squares and geometric elements became more prominent in Mackintosh’s work from the 1900’s and this can be seen with effect at Mackintosh at the Willow. The original willow tea room building arguably demonstrates the best example of the meeting point between his established softer style and his developing preoccupation with geometry. Hous’hill was decorated by Mackintosh for Miss Cranston in 1905 and perfectly demonstrates the artist moving towards a more exact clarity of form that would later culminate in creations such as the Dug Out of Mackintosh at the Willow in 1917.

Fantasy plays a huge role in the work of Mackintosh and was represented with the whimsical aspects of nature or by mythological and symbolic imagery. Mackintosh’s father was said to be an avid gardener and the house would always be filled with flowers, something that Mackintosh would draw great inspiration from, especially in his multitude of watercolours. However, there is one very prominent watercolour produced by Mackintosh that may have had influenced the square design technique. The painting, named Fritillaria, is now in the Mackintosh Collection at the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow. The water colour and pencil composition display delicate flowers belonging to the lily family. Four flowers are presented in various angles, painted purple and, when examining the detail, the viewer can clearly see the little checked pattern that adorns their petals. This has been noted by Mackintosh with importance as he has added a chequered strip, highlighting this significant meeting of design and nature.

Trellises can be seen influencing a multitude of design features in the original Willow Tea Rooms building. They are commonly used as an architectural element in gardens to support vines and similar plants to ensure they grow vertically. As mentioned in our previous blogs, the concept applied to much of the design work in the building is the Willow Tree and, as a result, we experience aesthetic properties that create the visual effect of the whole building growing upwards. The trellis continues this theme and the use of square geometry in its form structures the otherwise very natural and soft elements of the building. The dark wood or paint used to create the trellis designs align them with Japanese interiors, more specifically the paper screens used to create privacy in Japanese homes. These are called shoji. In 1858 there was a forced reopening of trade with Japan, leading to surge of Japanese influence on Western art and culture. This was eventually termed Japonisme by French art critic and collector Philippe Burty in 1872 and was to become a strong feature in Art Nouveau work. One of Mackintosh’s biggest influences was also the likes of Aubrey Beardsley. Beardsley was a leading figure in the development of the Art Nouveau movement and his art was heavily inspired by Japanese woodcuts.

Mackintosh lends a subtlety of touch to his rooms that demonstrates an understanding of the psychology of space on the consciousness. The clean lines applied to geometrical shapes continue this air of serenity with their satisfying precision and clarity, linking all spaces seamlessly. The Front Salon, when viewed from the rear of the building, is backed by the windows of the buildings frontage which creates a backdrop of glass squares. The carpets of the Back Saloon, the Salon de Luxe and the Billiard Room all display carpets with the square pattern weaved through the design. They are linked together by the carpets of the stairs which incorporated the same pattern. In the Gallery and the Billiard Room stencilled square patterns adorn the walls and decorate the light fixtures.